Angot is a historically pure Amhara sub province which withstood multiple invasions which led to the creation of a unique warrior culture.

This article will focus on the ethnic habitants of Raya originally, the language spoken, the boundaries and the history of Angot from the 14th century to now.

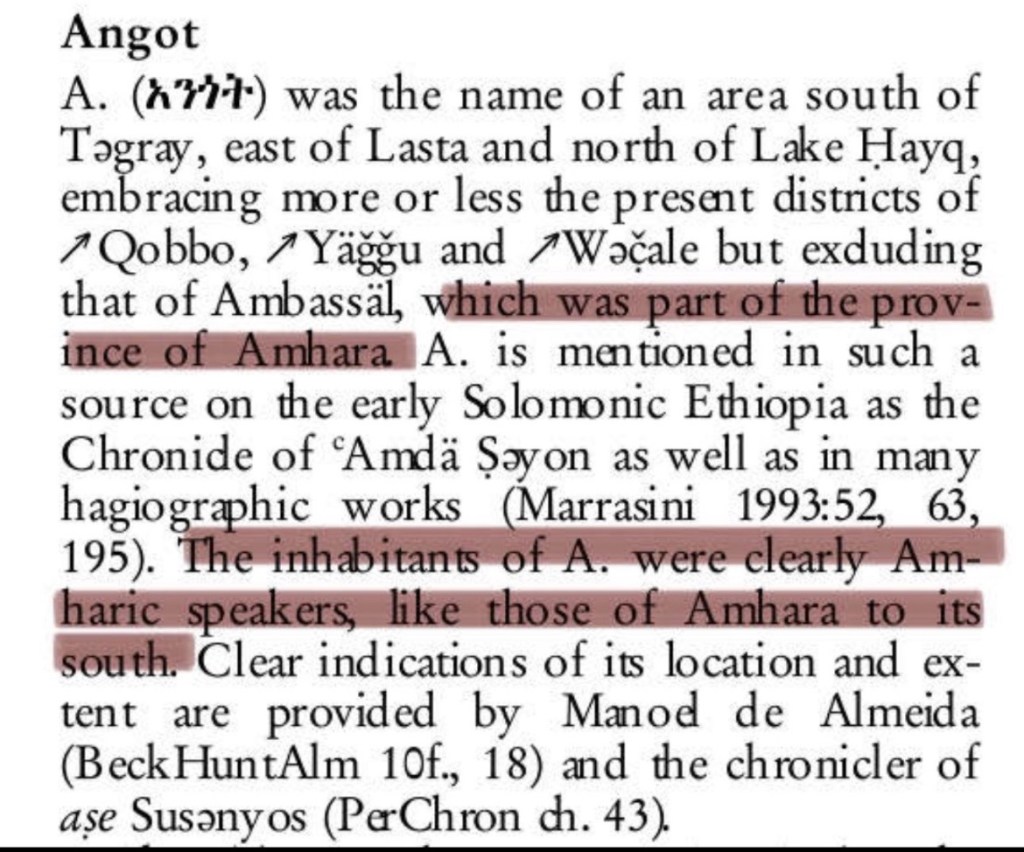

Angot was always an Amhara province.1

Angot an Amharic term (አንጎት), translated as “Neck” due to its geographical location was a medieval province part of the Ethiopian empire.2

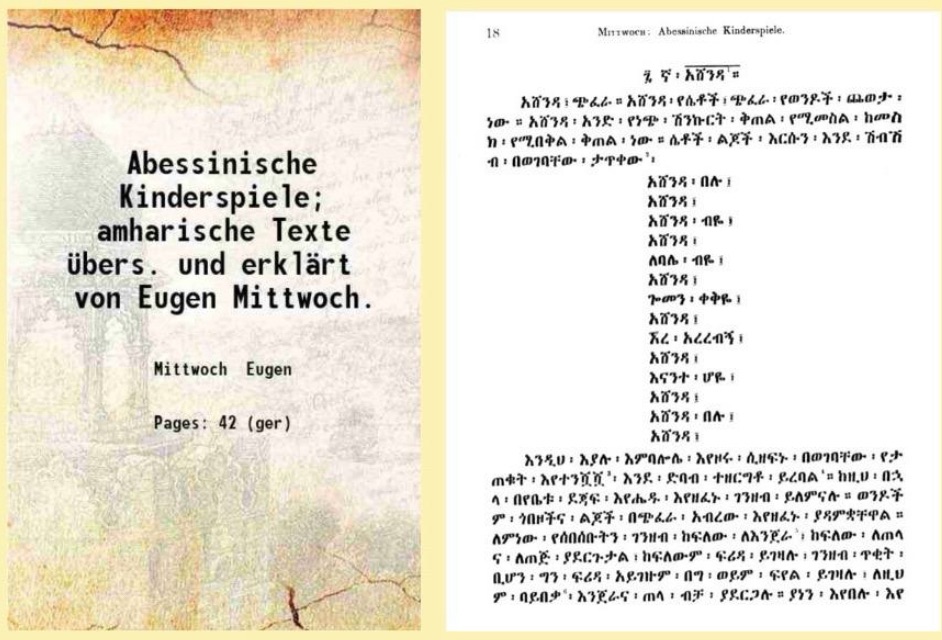

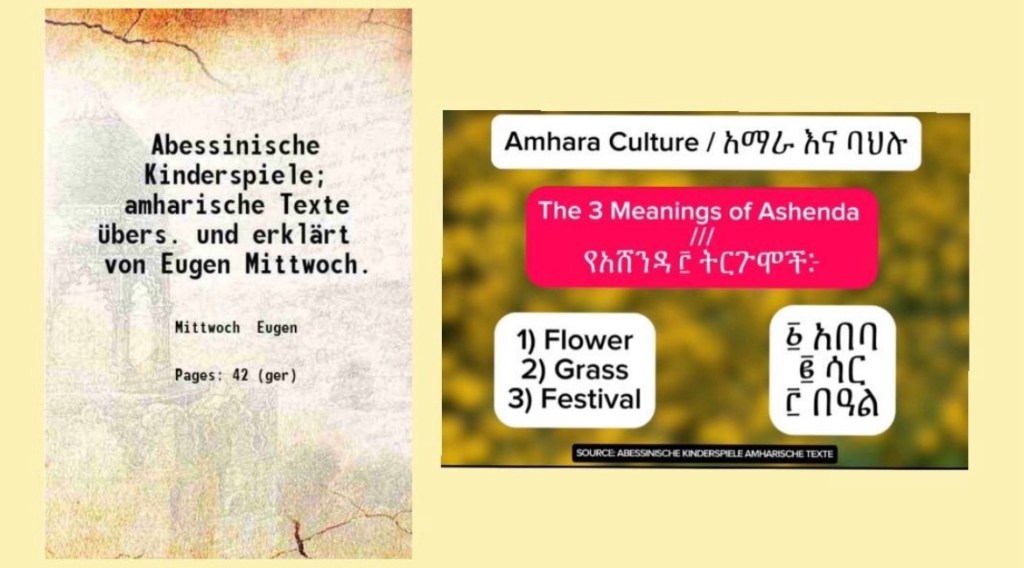

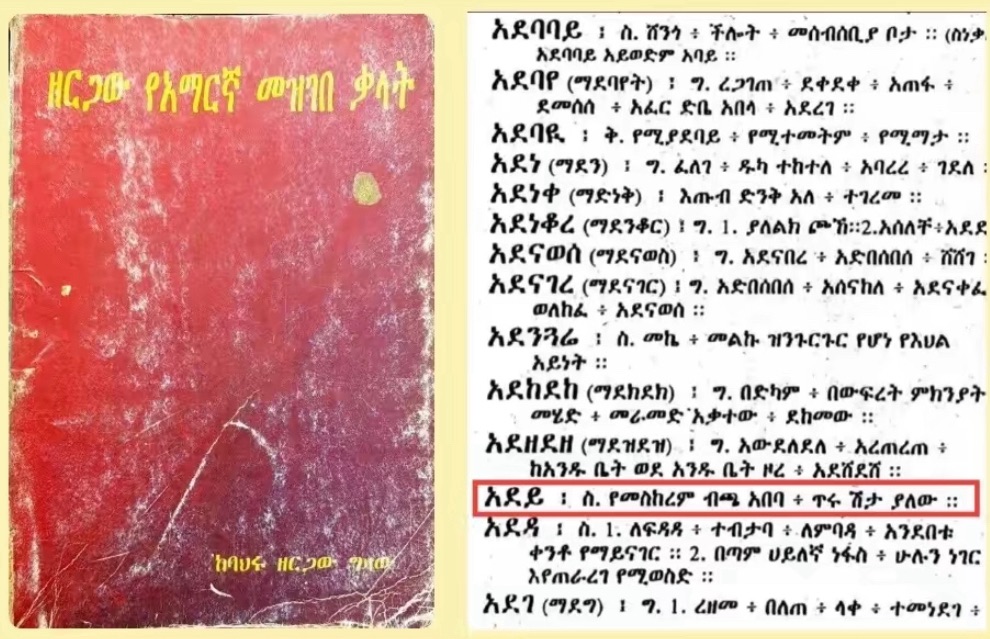

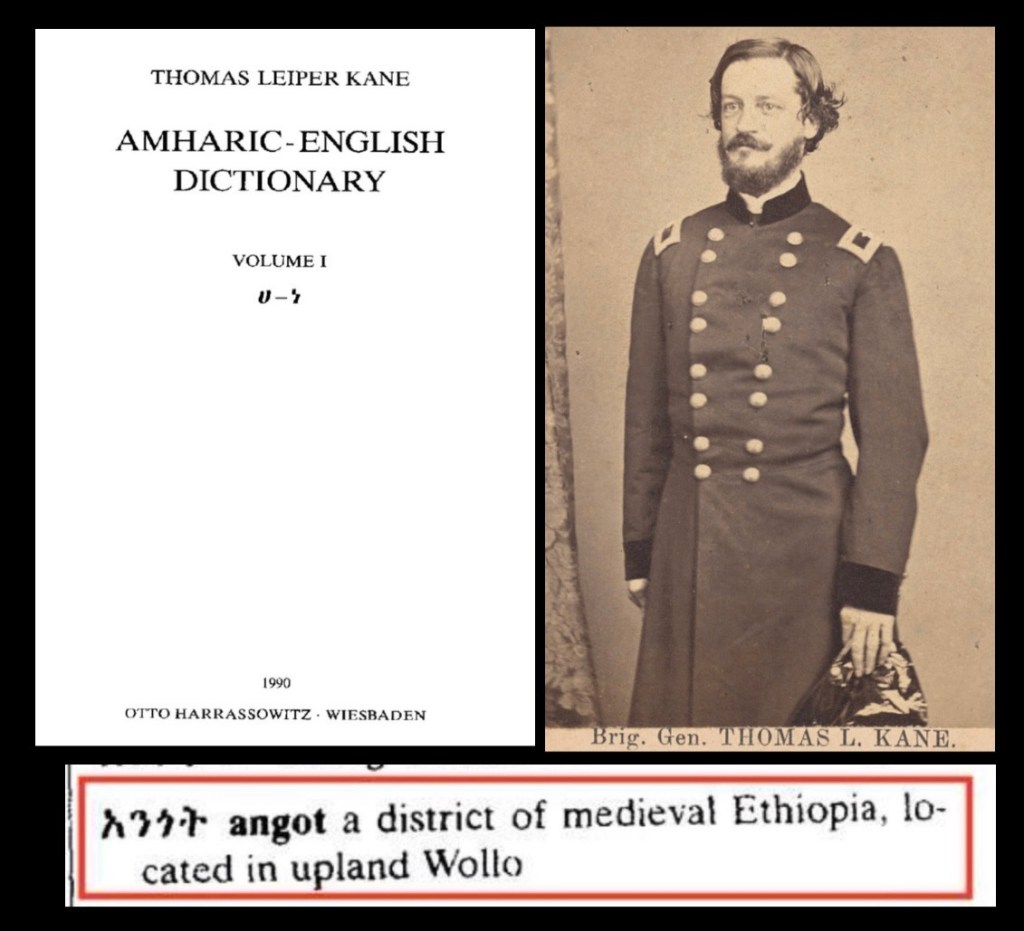

Additionally this Amharic dictionary first published in 1948 states that Angot was ‘located in upland wollo’.3

Angot is first seen in the chronicles of Amde seyon (1314-1344). In contrast to how tigrayn nationalists claim that angot/raya has always been their land, we see that it is listed as seperate province.4

Below is examples of Angot being mentioned in an Amharic victory poem in the chronicle of Amde Seyon I.

In modern times some residents of Raya have been mislead to believe that they are descendants of doba people however this is quite frankly wrong in multiple ways as I will show throughout this thread. This map shows Ethiopia during the reign of Amde Seyon I (1314-1344).5

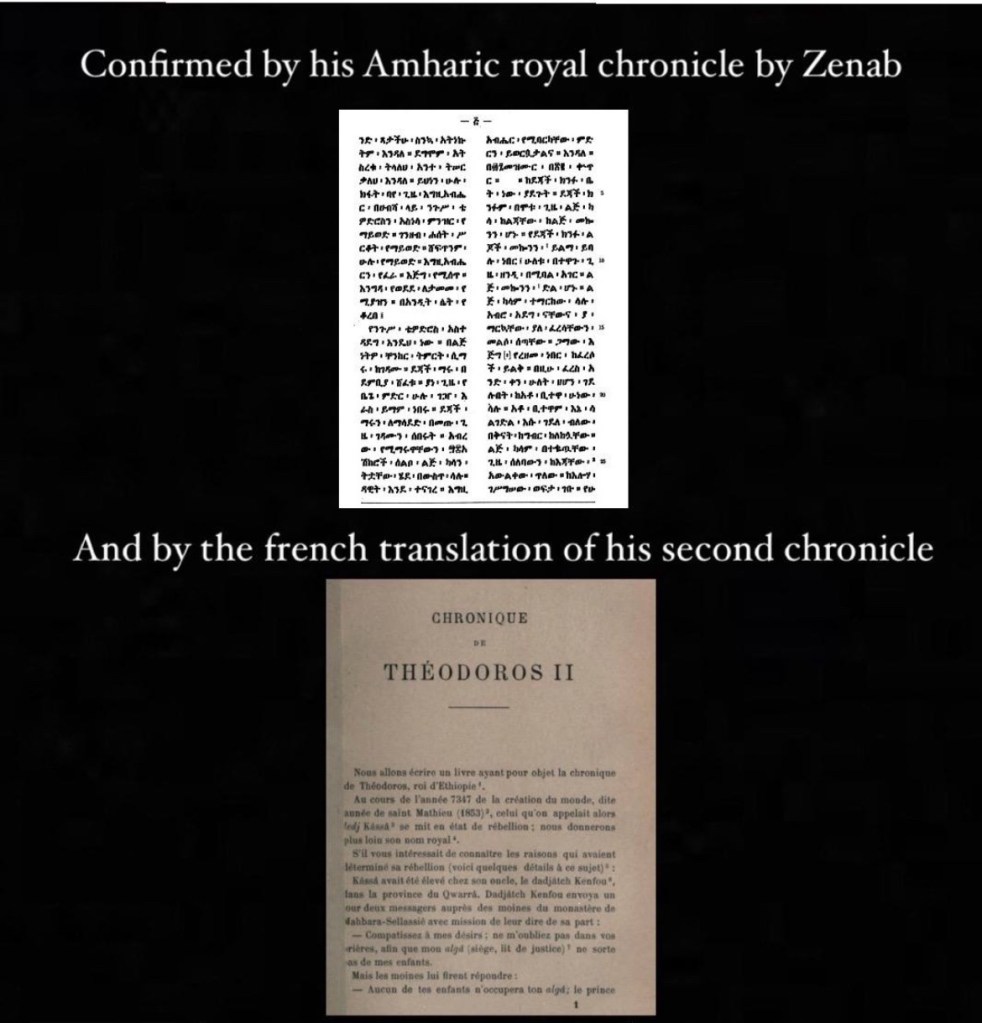

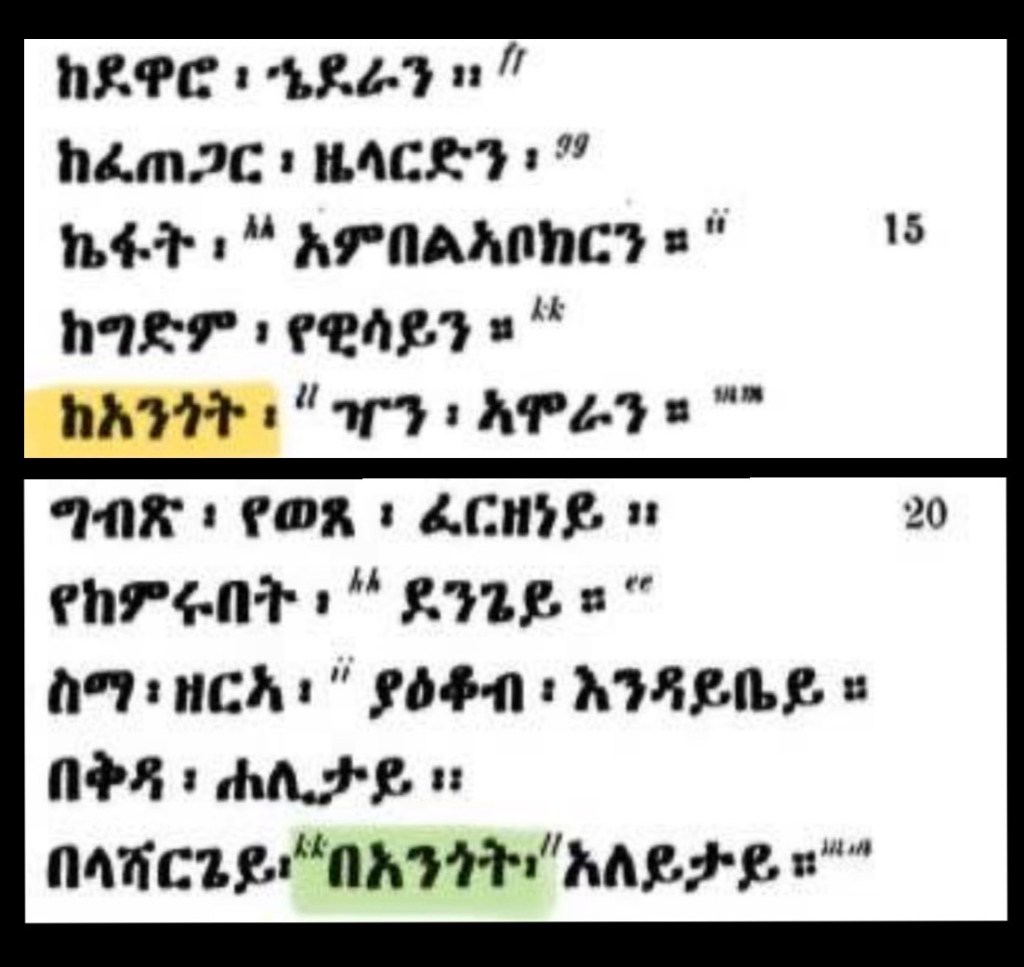

To prove further the distinction between the tigrayan provinces and angot we see during Zara Ya’qobs reign that he appoints new rulers in the form of his sisters in the provinces of Ethiopia. (Amharic and English)6

The Egyptian Novelo map published in Florence in 1454 reinforces this point.7

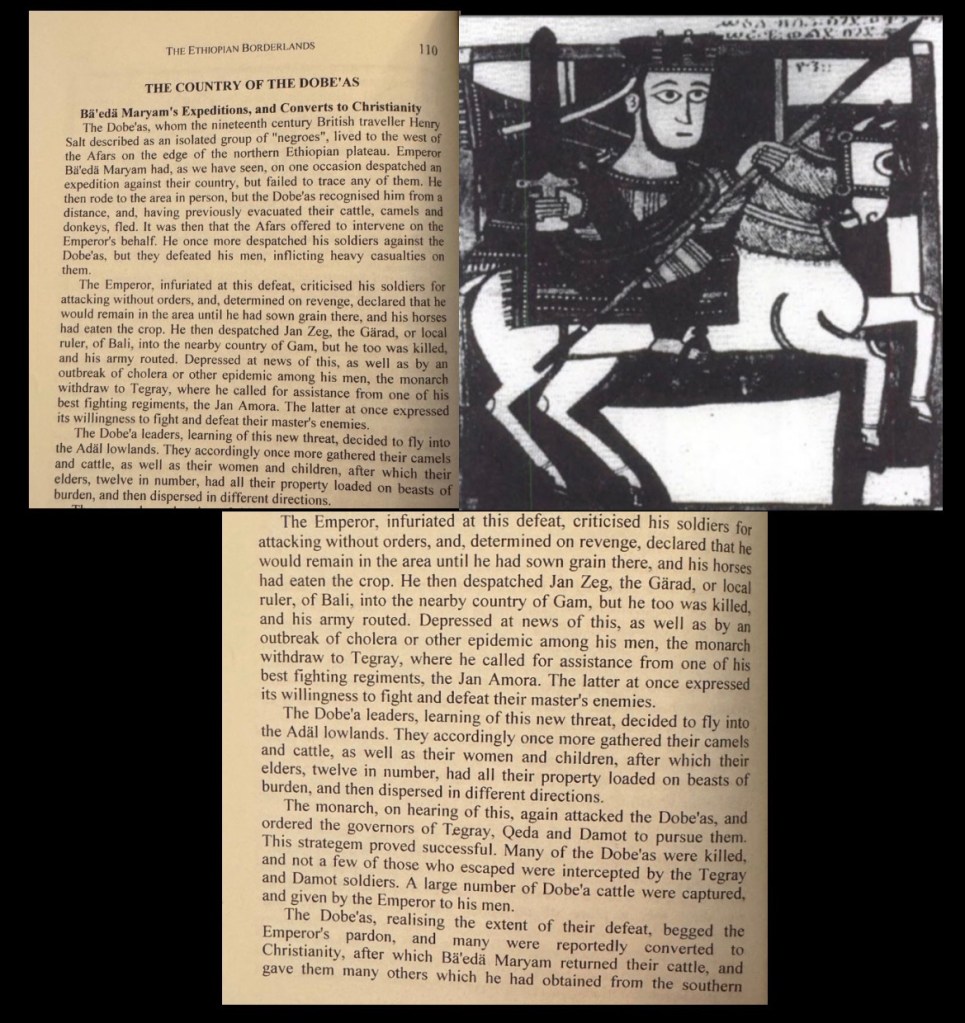

Baeda Maryam (1448-1478) the emperor following Zara yaq’ob through his campaigns evidently shows us that the doba people are not Amhara and were actually in war against the Abyssinians and the Afar people too as shown below.8

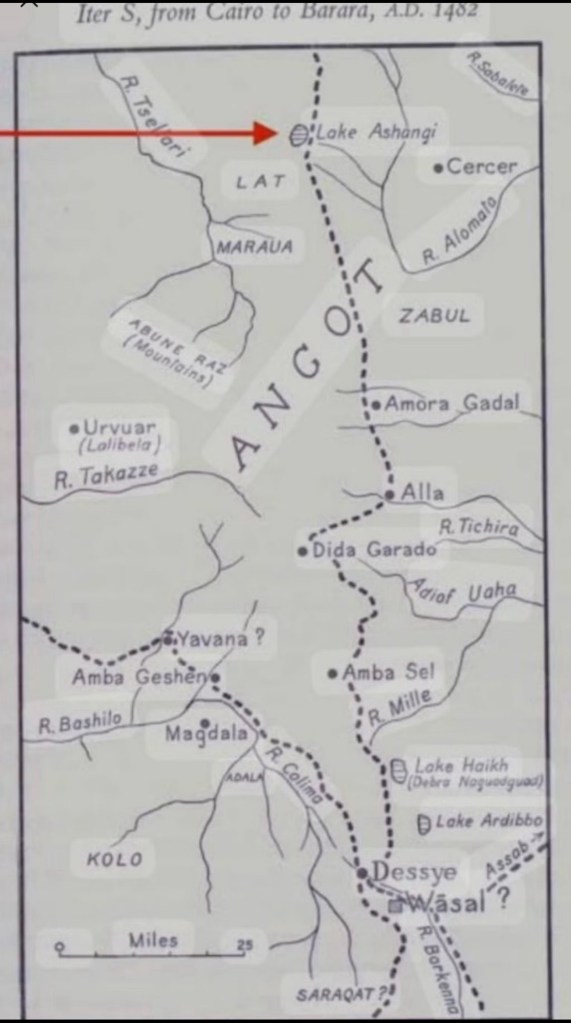

A map showing angot specifically from 1482 shows modern towns such as chercher (cercer) and is in agreement with the description later provided by transition Alvarez regarding the border being the river sabalete. Doba is also not present.9

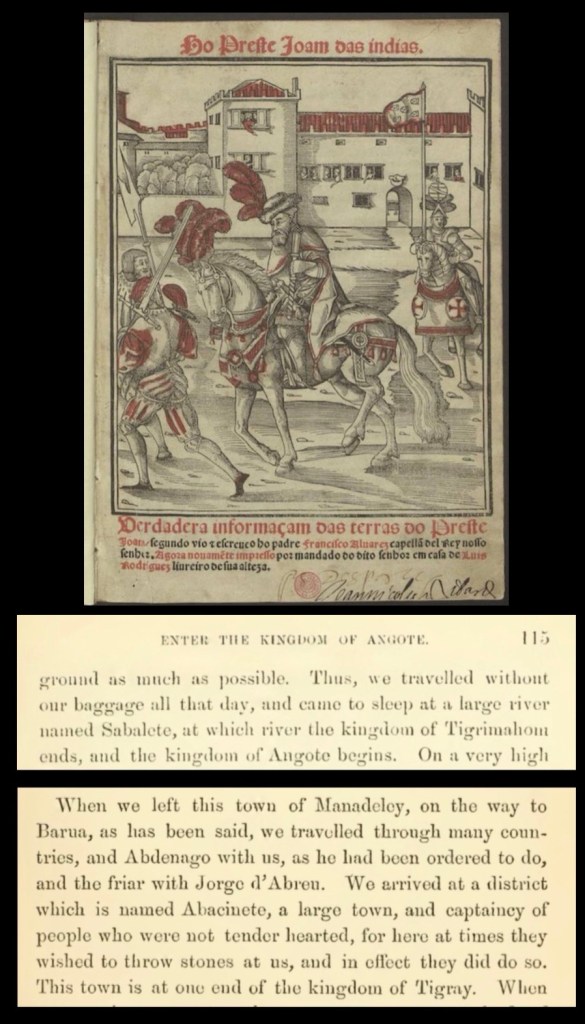

The next refrence to angot we see is by missionary Fransisco Alvarez

Below are his own descriptions of the boundaries of tigray and angot.

“and came to sleep at a large river named Sabalete, at which river the kingdom of Tigrimahom ends, and the kingdom of Angote begins.”10

These boundaries are also shown on a map based off his travels.

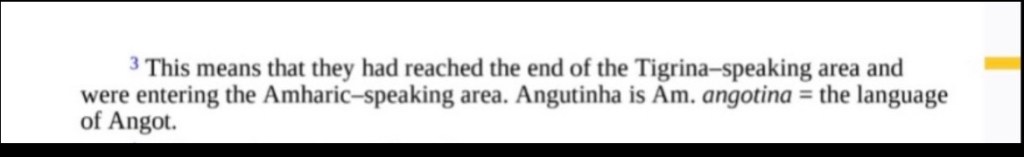

Francisco Alvarez also tells us that once he reached the kingdom of angot the people spoke Amharic. This shows the inhabitants of Raya were Amhara.11

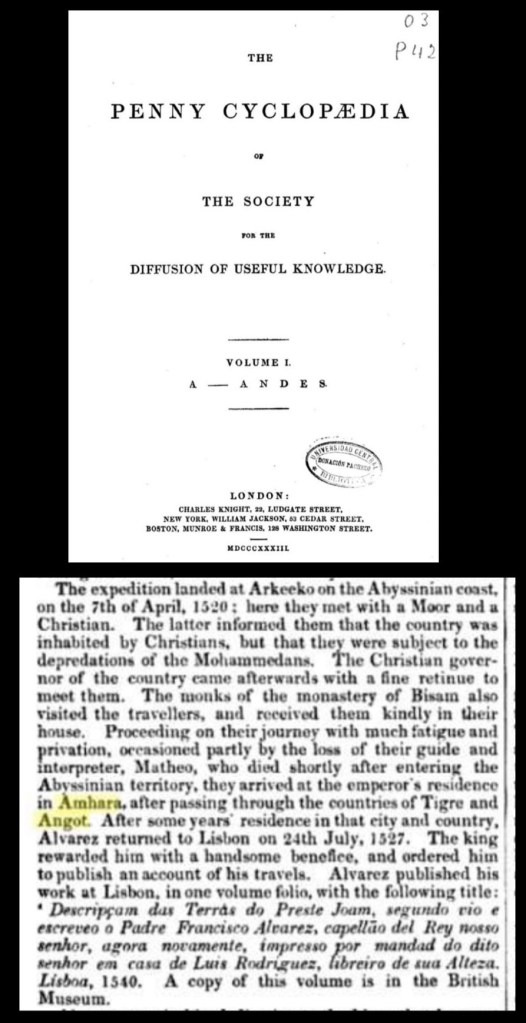

Description of the route the Portuguese contigent during the Ethio-Adal war took from the Abyssinian coast.12

These territories are confirmed in G.W.B. Huntingford, “The Historical Geography of Ethiopia,” which cites Emperor Libne Dengel (Dawit II) (1508-1540) himself describing his kingdoms.

“Aksum to wajrat”13

This map from 1550 during the reign of Gelawdewos the emperor (1540-1559)

The Distribution of royal churches and monasteries (13th-16th century) confirms this.

The inhabitants of angot are also clearly stated in the book Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916 it states “Weresh/Yejju are the results of various layers of people: the Amhara of Angot..”14

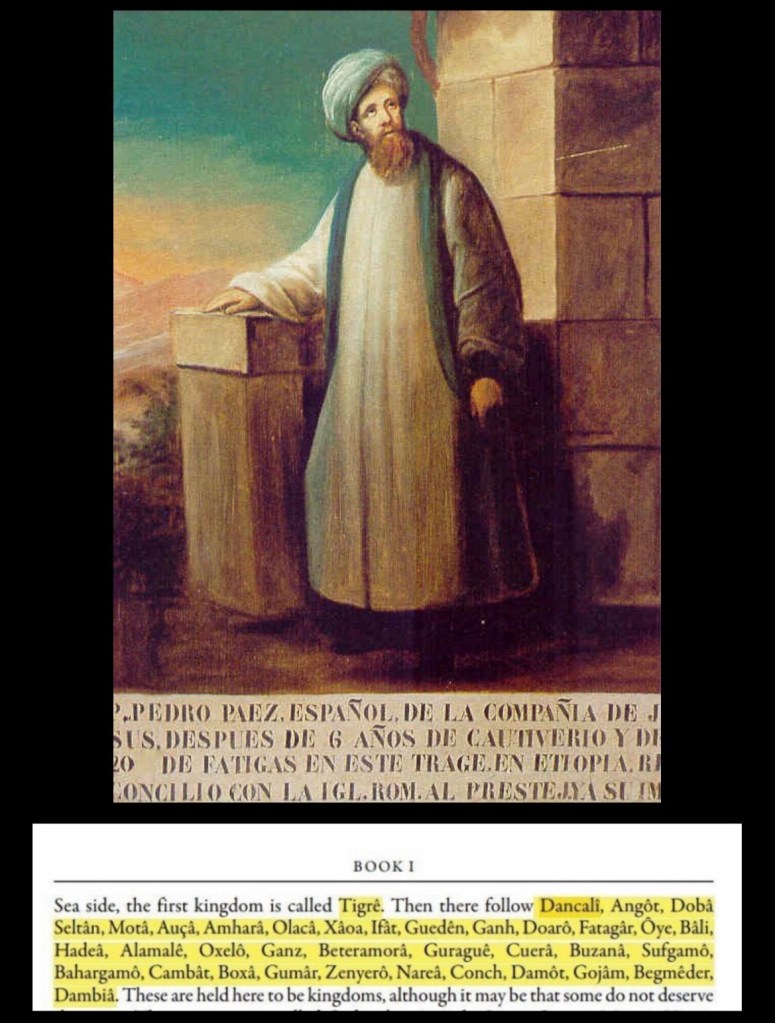

Spanish missionary Pedro Paez (1564-1622) in his book “History of Ethiopia” lists Angot and Tigre as separate kingdoms.15

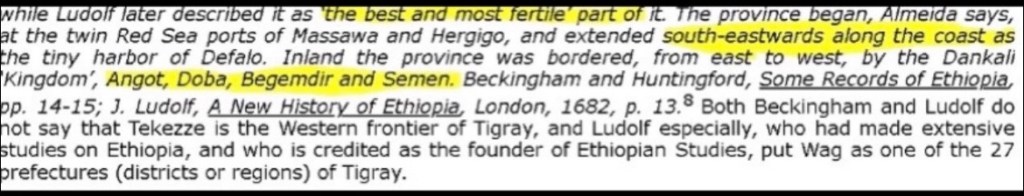

Another Portuguese missionary Manuel de Almeida (1580-1646) described the borders of Tigre and portrayed this in his own map.16

Manuel de Almeidas own map below reiterates this.

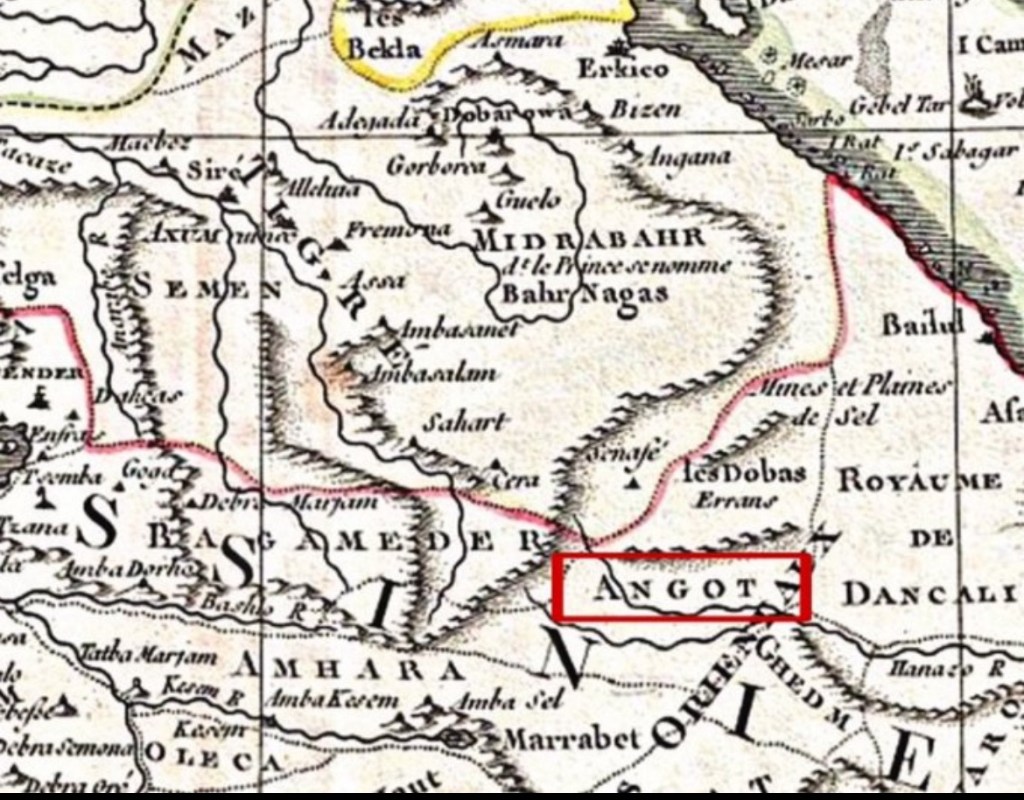

In Gérard Mercator’s map “Abyssinoum sive Preciosi Johannis Imperium,” published in 1607, Angot again is shown as an individual kingdom in Ethiopia.17

In the book Description de l’Afrique published in 1686 it states ‘south of Angot is Amhara’ which means Angot is not part of Tigray since it would say south of Tigray instead’18

A few years later In Vincenzo Coronelli’s map of “Ethiopia, Abyssinia, and the Source of the Blue Nile” (1690), Angot is again not a part of Tigray and is in close proximity to the province of Amhara (Bete Amhara).19

Lastly, Oromo writer Mohammed Hassen admits who the inhabitants of Angot were before the Galla incursions into Ethiopia.

Moving on to Angot in the 17th century and onwards Didier Robert de Vaugondy’s (1688-1766), antique map of Abyssinia, Angot as well as other provinces are shown separate from Tigray, which is labeled Roy de Tigre.20

James Bruce (1730-1794), a Scottish traveller, confirms Amharic being spoken in Angot.21

In Rigobert Bonne (1727-1794) map of Abyssinia (1771), Angot is shown in proximity to Begemeder, the Danakil, and Amhara (the province).22

This source from 1769 states the language spoken in Angot.23

To continue, page 39 of the Edinburgh Encyclopedia (1830) describes the borders of Tigre.24

Despite the Oromo incursions in the 16th and 17th century, the language spoken within Angot continued to be Amharic.25

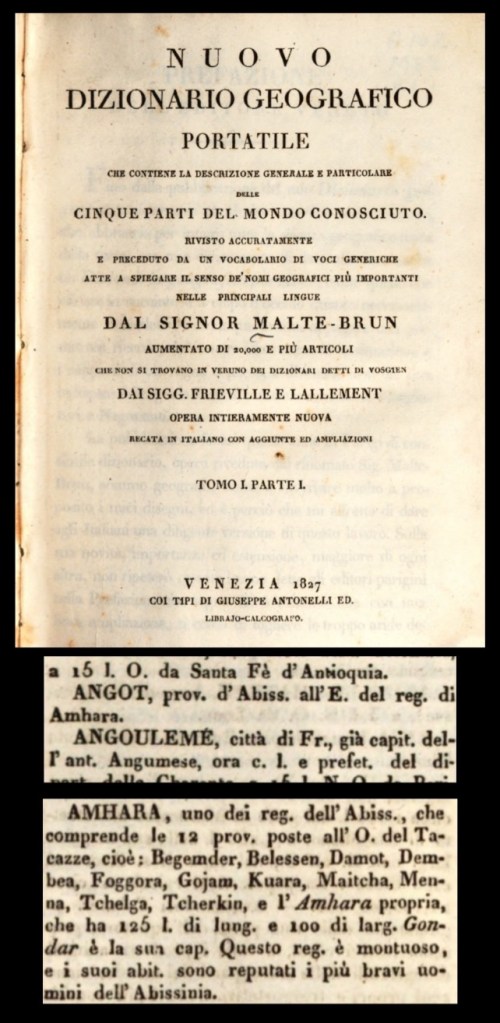

An Italian geographic book from 1827 shows both Angot and Welkait as apart of Amhara.26

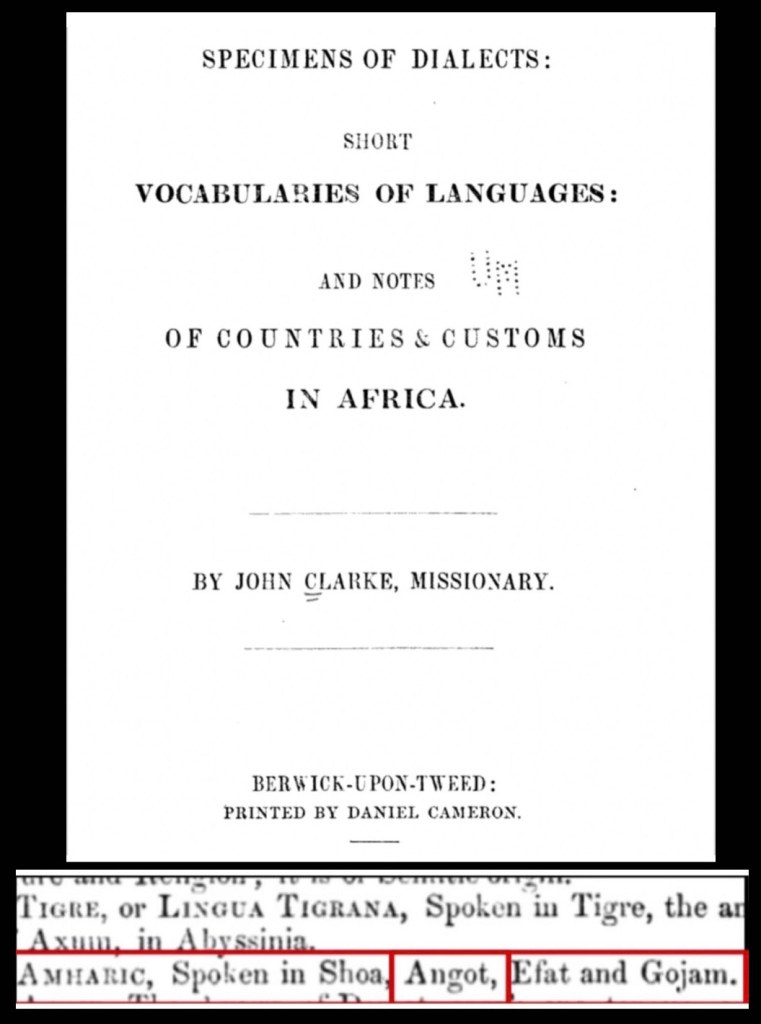

To add on page 100 of the book Specimens of Dialects, Short Vocabularies of Languages: and Notes of Countries & Customs in Africa, written by John Clarke (1848), it explicitly states that Amharic was spoken in Angot.27

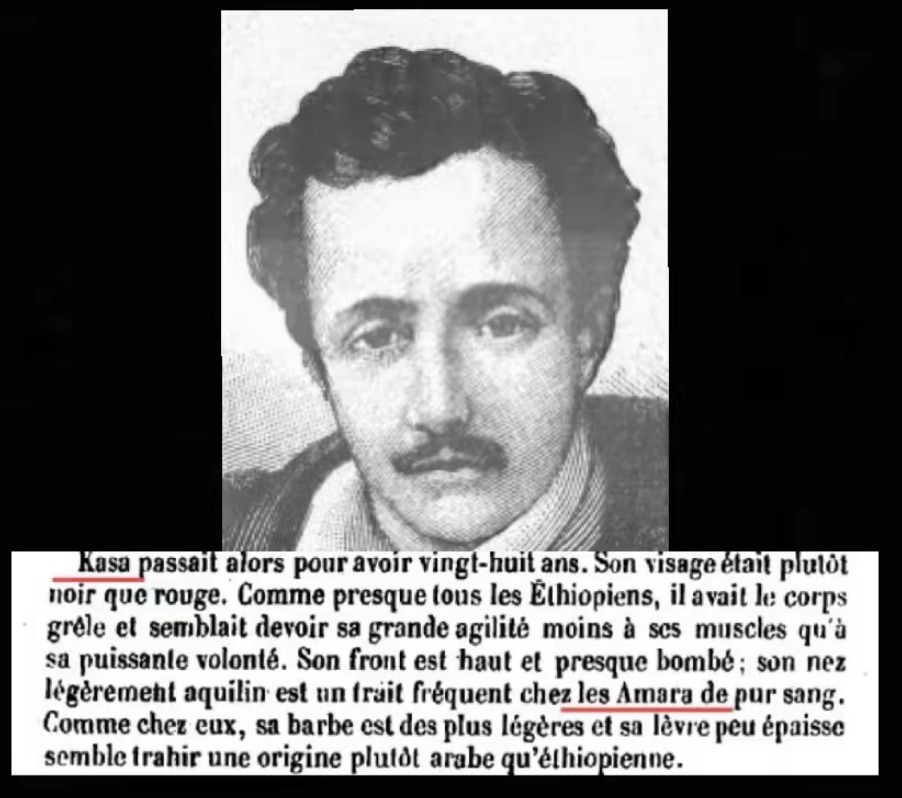

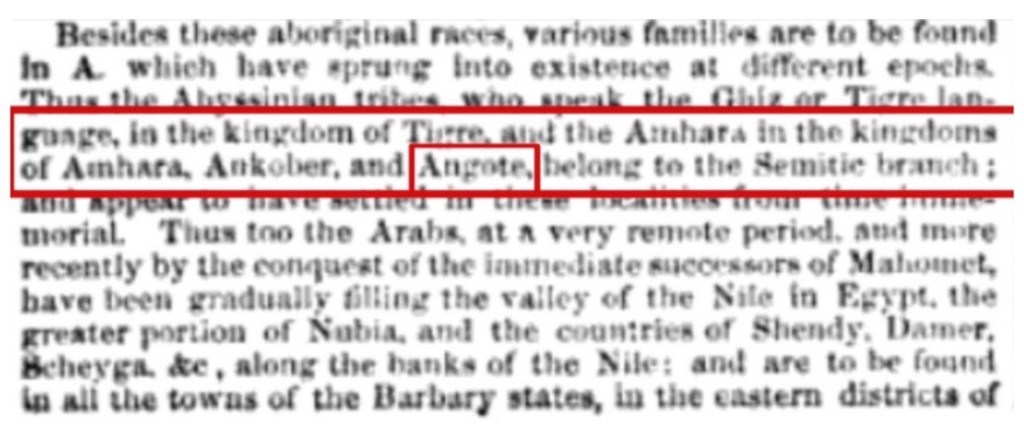

From the same year, page 39 of the book : Plowden, Walter Chichele, and Trevor Chichele Plowden. Travels in Abyssinia and the Galla Country: With an Account of a Mission to Ras Ali in 1848.28

Page 25 of A Gazetteer of the World, written by A.A. Braze (1856), states the inhabitants of Angot as Amhara.29

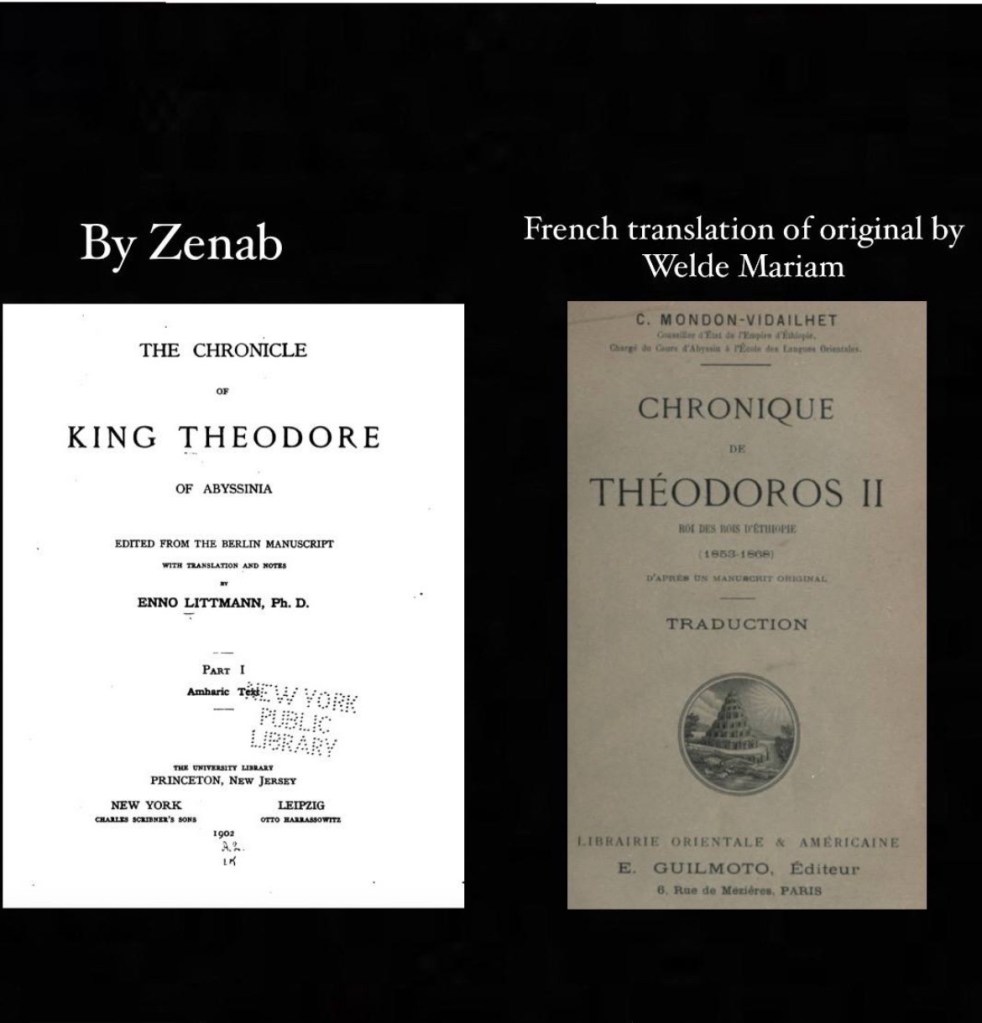

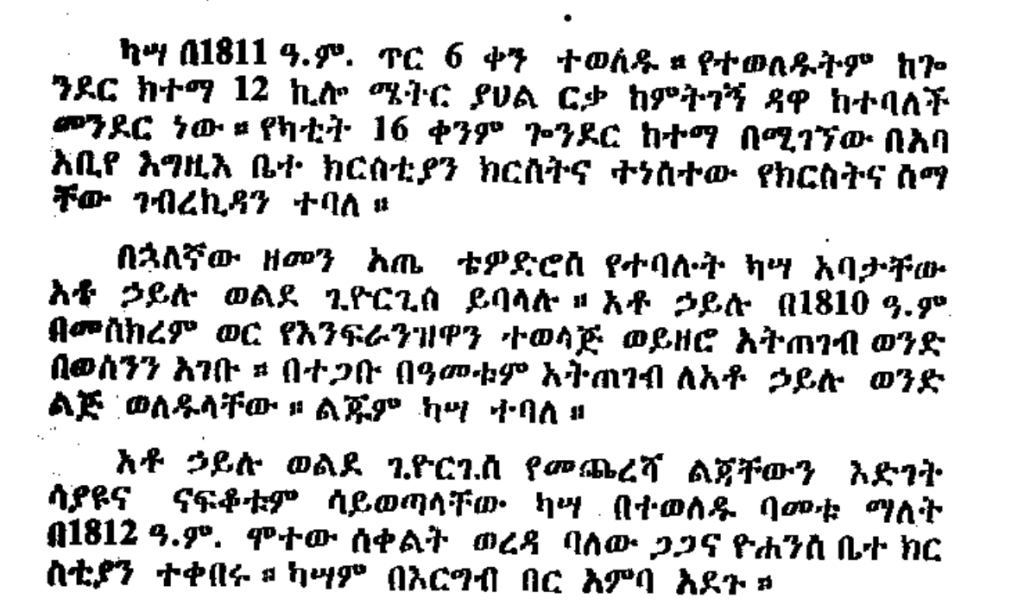

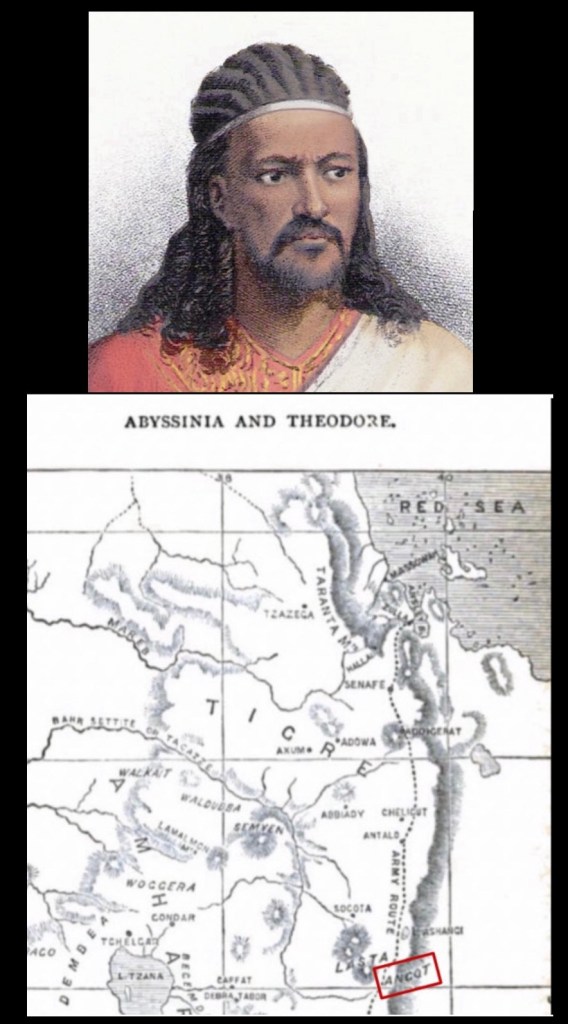

Under Emperor Tewodros II, the former boundaries of regions within Ethiopia were restored, and Angot remained an Amhara province.

Angot’s borders are described to have a river as a border from Tigray as described by Fransisco Alvarez. Source : British and foriegn state papers 1863-1864 Vol LIV. William Ridgway.30

An Italian source from 1875 which also coincides during Yohaness IV reign states everything west of the tekezze including amhara proper, dembea, Gojjam, Damot, wellega, begemeder, Angot, semein, waldeba and welkait is part of Amhara.31

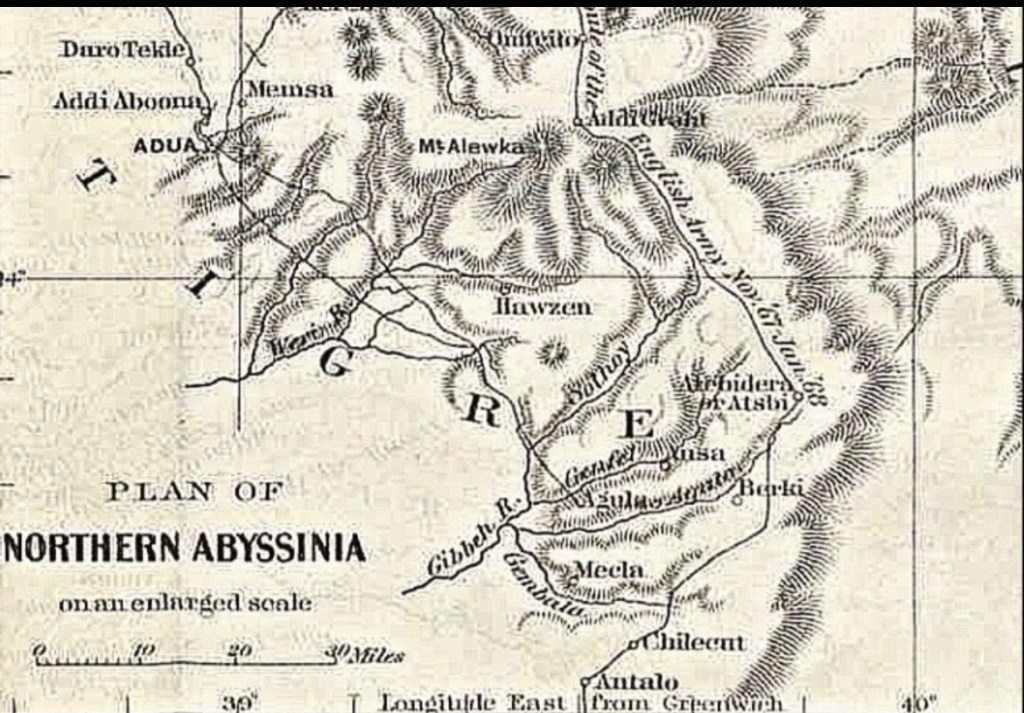

Boundaries of Tigre (Tigray) during his reign (Yohannes IV).32

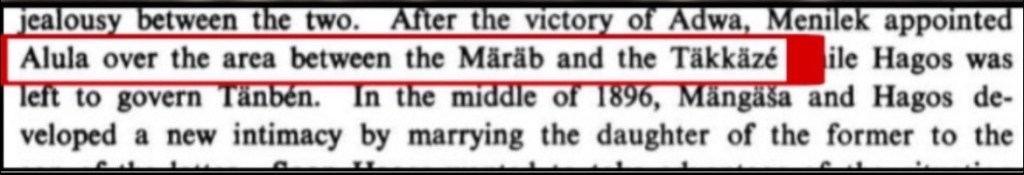

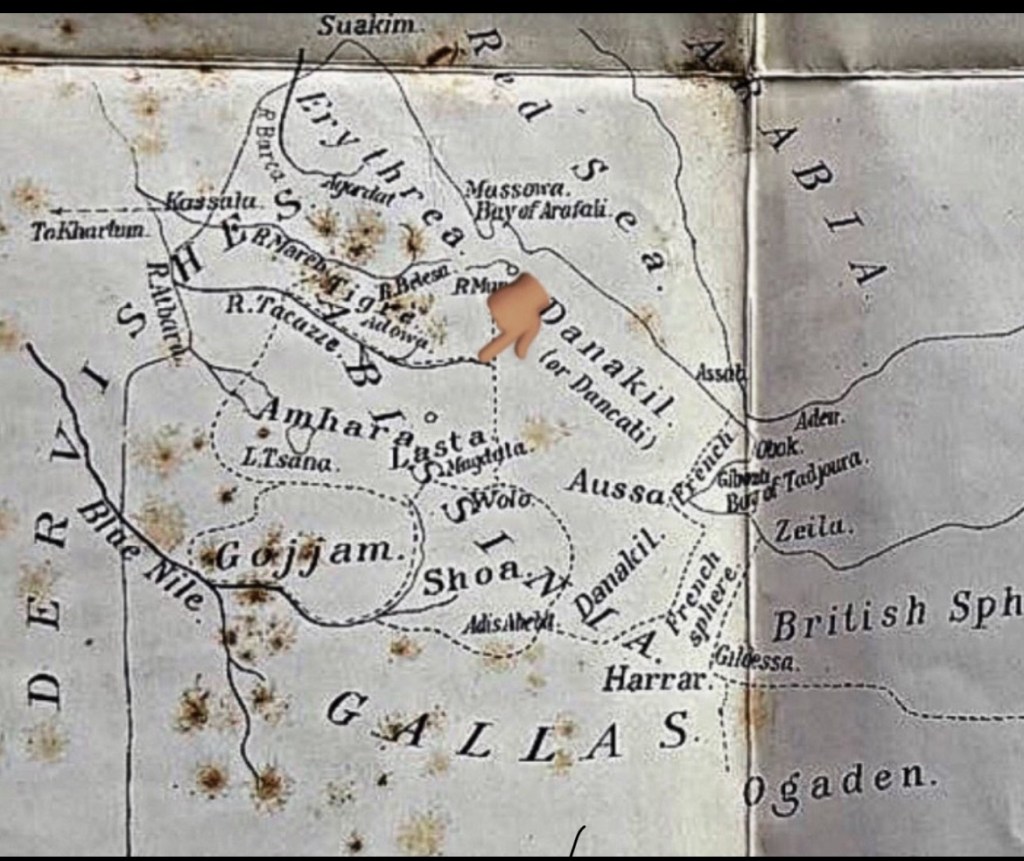

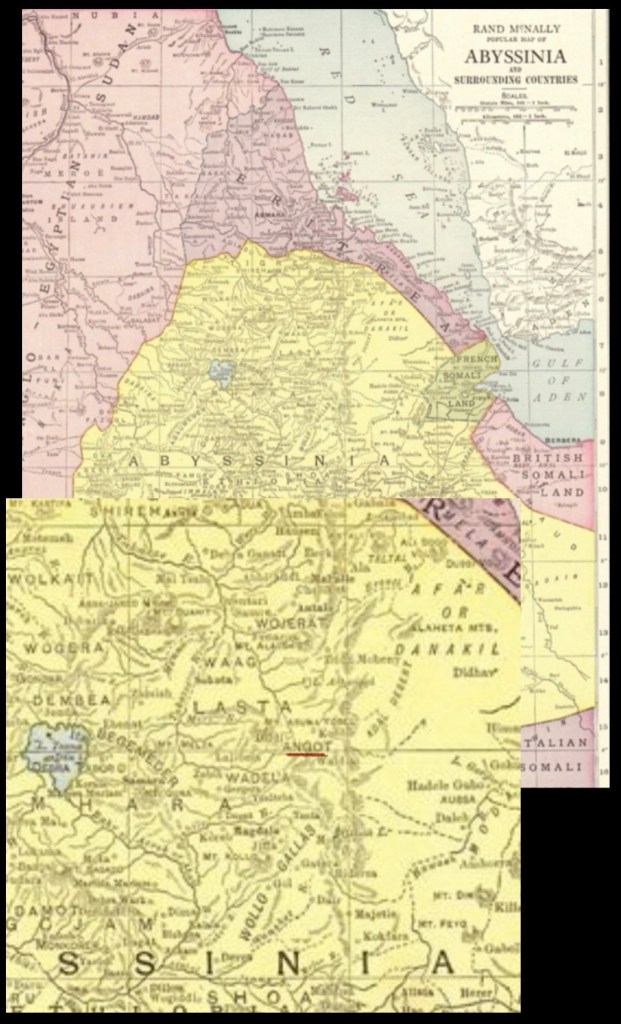

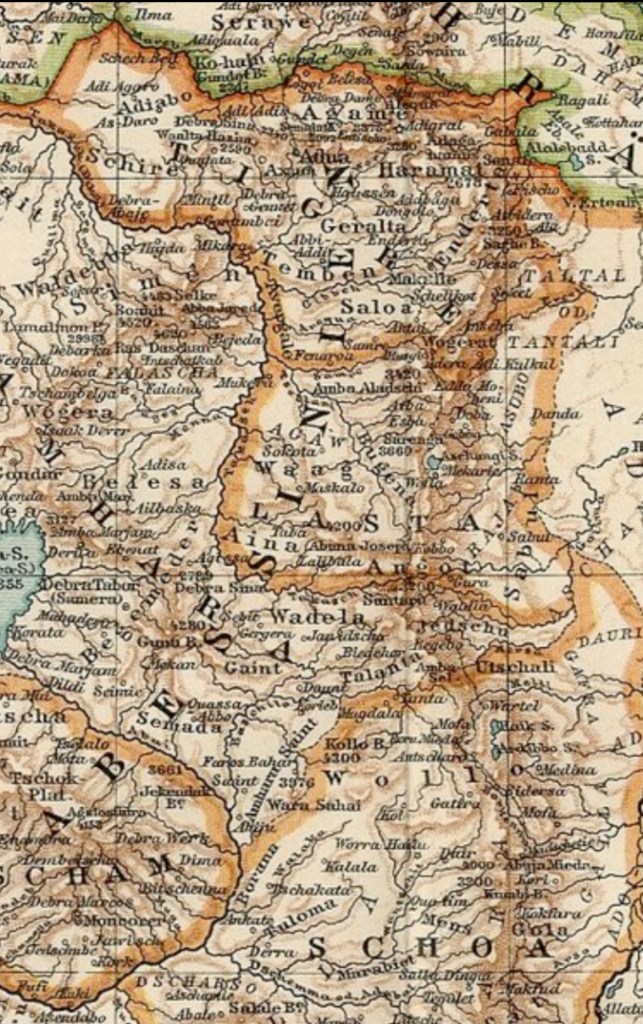

Similar to Yohannes, under Menelik II (1889-1913), Angot was under Wag/Lasta administration within Amhara. Tigray administration was noted to be between the Mareb and Tekeze with its ruler as Ras Alula.33

Map of Ethiopia under Menelik

Text source for the map:

Another Map of Ethiopia under Menelik II showing the same thing.34

This map of Ethiopia from the early 1900s after Menelik shows Angot continues to be under Lasta.35

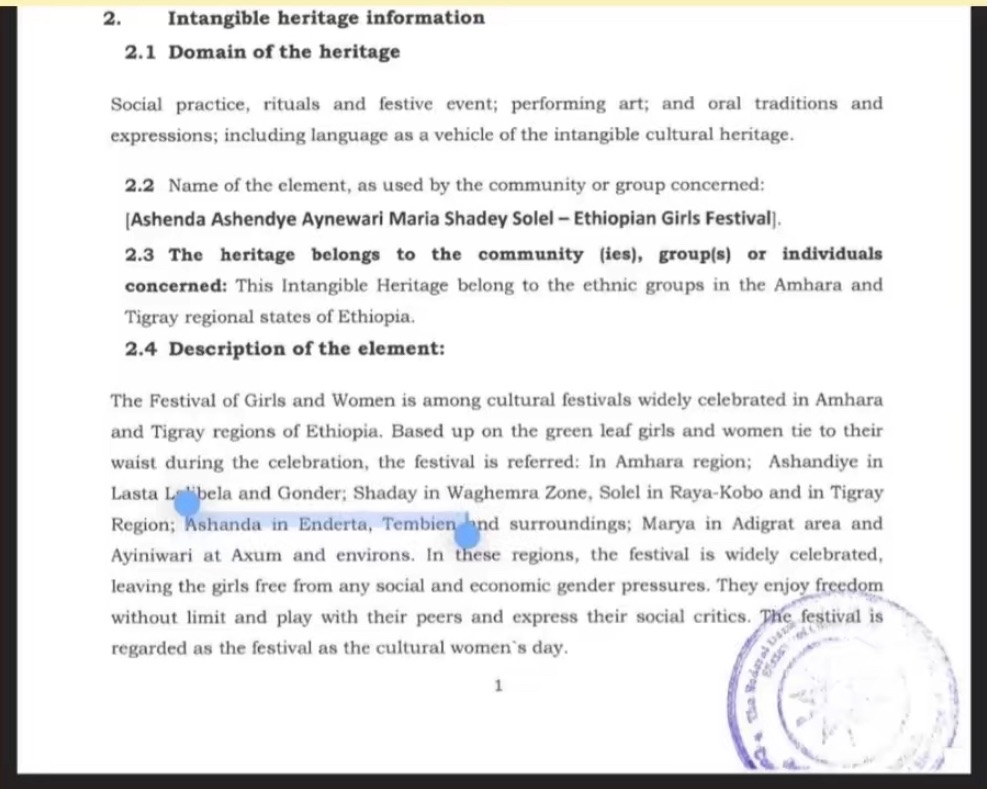

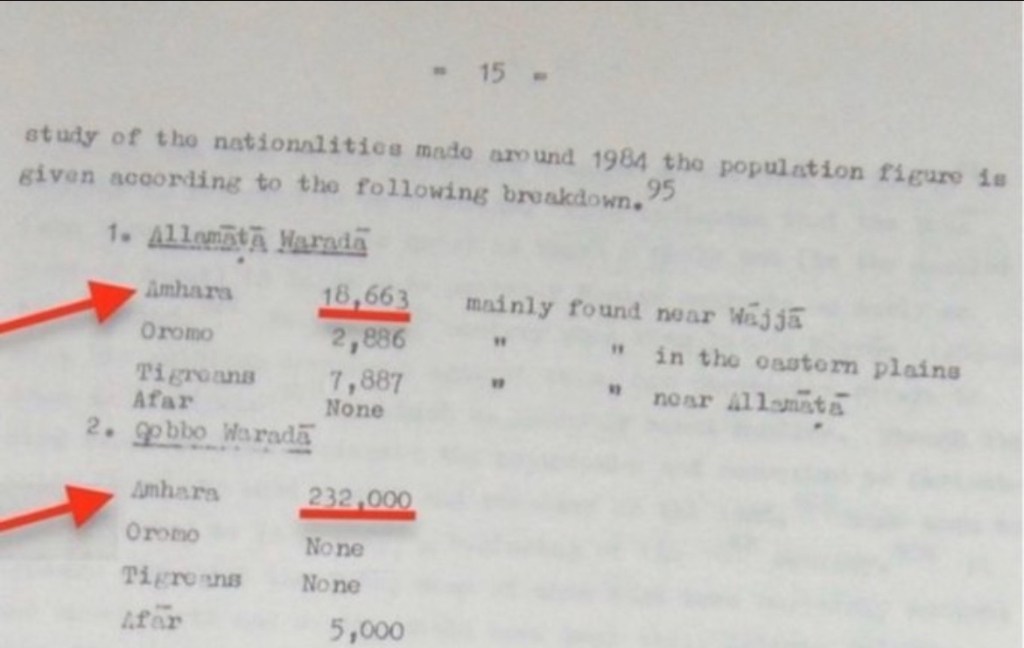

Population Statistics from the Derg period in Alamata and Kobbo showing that Amharas are the majority.

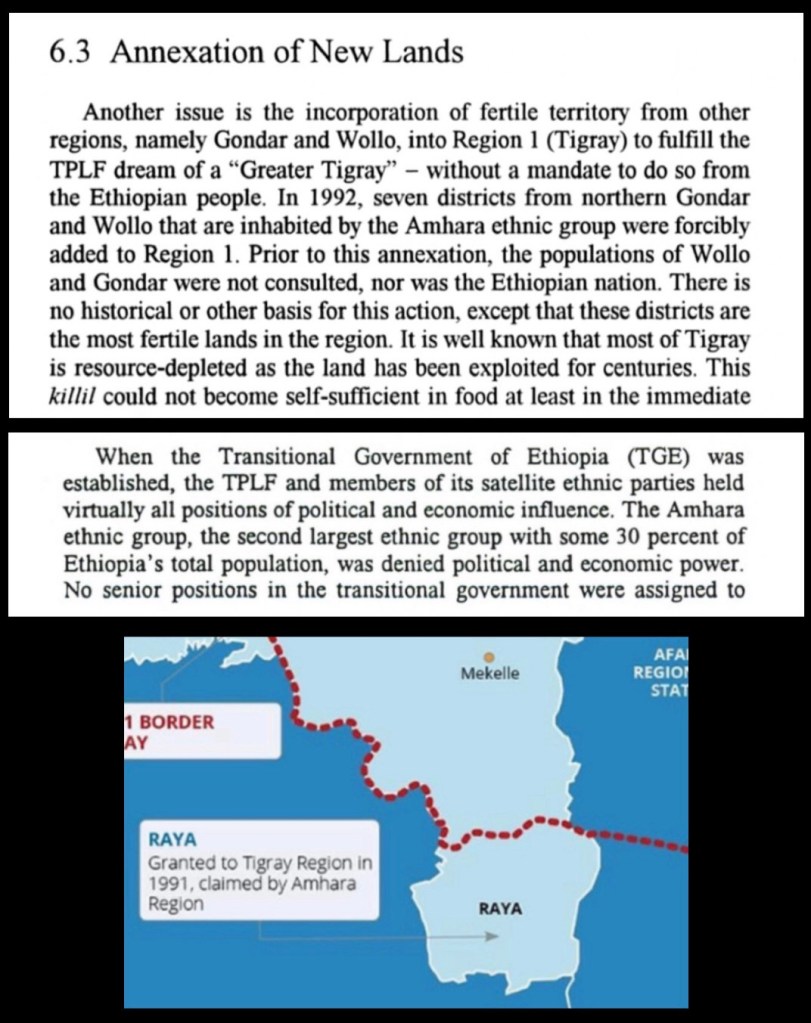

After the Derg fell, the TPLF forcefully annexed Raya (as well as Welkait) and incorporated it into Tigray. This was done in a similar process to migrants in Welkait. The migrants being tigrayns were incoproated into the region while the indigenous Amharas were cleansed.36

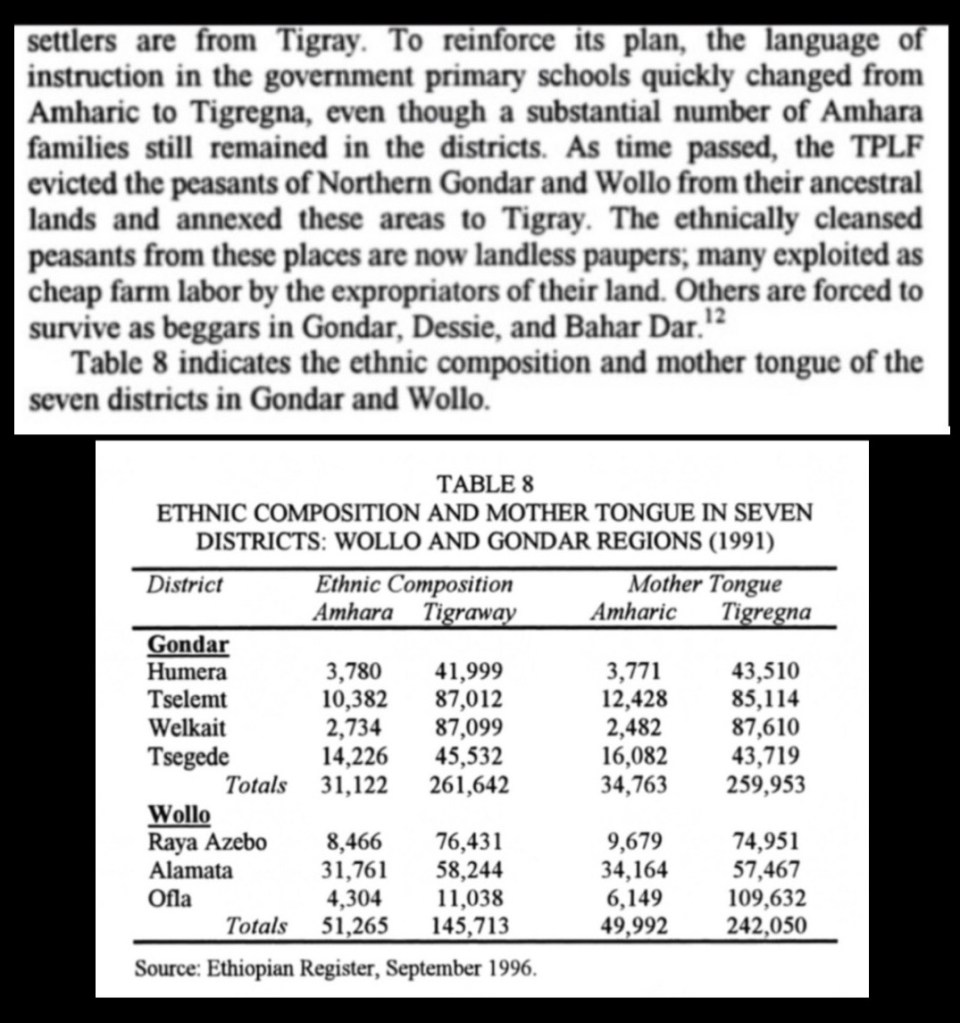

Tigrayn nationalists will also use this deceptive table. What they dont show you is how amhara citzens were ethnically cleansed and evicted.37

Continuing, the citizens of Raya are stated to identify with the Amhara regional state and Ethiopia and not with the Tigray regional state.38

The TPLF regime’s control over the strategic and fertile Amhara land, including Angot(Raya), led to systemic oppression. To maintain dominance, they imposed displacement, forced assimilation, and a form of apartheid. The people of Angot, who identified as ethnic Amhara, were forced to receive education in Tigrigna under TPLF occupation and faced severe employment discrimination due to systemic racism. Additionally, corrupt Tigrayan officials exploited the local population through land seizures, extortion, and forced labor.

Under TPLF rule, Tigrayan officials systematically oppressed the Amhara population in Raya through coercion and cultural erasure. They issued death threats and extorted locals, forcing them to make arbitrary payments beyond their means—even compelling them to sell their livestock to drain their resources. Meanwhile, the imposition of Tigrigna as the sole language of education made learning nearly impossible for Amharic-speaking children, further entrenching systemic discrimination.

Under TPLF occupation, the Amhara population in Raya faced systematic oppression, including forced labor, ethnic marginalization, and cultural suppression. Tigrayan officials arbitrarily imprisoned locals with 20-year sentences to exploit them as unpaid laborers—effectively reducing them to slavery. Men were threatened with death unless they fled, while women were pressured to stay, likely as part of a demographic engineering strategy involving forced marriages.

Additionally, despite local opposition, Tigrayan authorities reinstated education in Tigrigna—a language most Raya residents do not speak—ignoring the Amhara community’s demand for Amharic-language schooling and administration under their rightful regional government. These measures reflect a broader campaign of displacement, cultural erasure, and subjugation.

In this video an Amhara man is talking about the experience of Amharas being forced to learn Tigrinya as part of the enforced Tigrinya identity.

An Amhara who was forced to learn Tigrinya explains the process of how in the past 30 years TPLF has tried to “tigrinize” Amharas. Angot land is very fertile that’s all TPLF care about. 90% of azebo land is controlled by Tigray investors.

In this video an Amhara woman from Raya is speaking about her identity and oppression from tplf.

The struggle to free Angot(raya) after decades of apartheid and oppression by the fascist TPLF government still continues and it will never end until the Amharas from Angot finally gain freedom.

- Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 1: A-C ↩︎

- Travellers in Ethiopia, Richard Pankhurst ↩︎

- Amharic dictionary first published in 1948 by Tefera Werq Armede, then adapted to Amharic-English and republished in 1990 by American Thomas Leiper Kane. ↩︎

- G.W.B. Huntigford the glorious victories of Amde Seyon I. ↩︎

- Tadesse Tamrat Church and state in Ethiopia 1270-1527 ↩︎

- Royal Chronicle of Emperor Zara Ya’qob ↩︎

- Richard Pankhurst The Ethiopian Borderlands : Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century ↩︎

- The Ethiopian borderlands Richard Pankhurst ↩︎

- Iter S, from Cairo to Barara, A.D. 1402 ↩︎

- Narrative of the Portuguese embassy to Abyssinia during the years 1520-1521. Father Francisco Alvarez. ↩︎

- The Prester John of the Indies: a true relation of the lands of the Prester John, being the narrative of the Portuguese embassy to Ethiopia in 1520, written by Francisco Alvares. ↩︎

- The Penny Cyclopedia of the Society for the diffusion of useful knowledge, Volumes 1-2, 1833 ↩︎

- G.W.B. Huntingford, “The Historical Geography of Ethiopia” ↩︎

- Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916 ↩︎

- Pedro Paez (1564-1622)”History of Ethiopia” ↩︎

- Manuel de Almeida (1580-1646) ↩︎

- Gérard Mercator’s map “Abyssinoum sive Preciosi Johannis Imperium,” published in 1607 ↩︎

- Description de l’Afrique published in 1686 ↩︎

- Vincenzo Coronelli’s map of “Ethiopia, Abyssinia, and the Source of the Blue Nile” (1690) ↩︎

- Didier Robert de Vaugondy’s (1688-1766) ↩︎

- Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, Volume 3, p. 693 ↩︎

- Rigobert Bonne (1727-1794) map of Abyssinia (1771) ↩︎

- Histoire moderne des Chinois, des Japonnois, des Indiens, des Persans, des Turcs, des Russiens,1769 ↩︎

- The Edinburgh Encyclopedia (1830) ↩︎

- The Penny Cyclopedia of the Society for the diffusion of useful knowledge, Volumes 1-2, 1833, p. 451 ↩︎

- Nuovo dizionario geografico portatile che contiene la descrizione generale e particolare delle cinque parti del mondo conosciuto ↩︎

- Specimens of Dialects, Short Vocabularies of Languages: and Notes of Countries & Customs in Africa, written by John Clarke (1848) p.100 ↩︎

- Plowden, Walter Chichele, and Trevor Chichele Plowden. Travels in Abyssinia and the Galla Country: With an Account of a Mission to Ras Ali in 1848. p.39 ↩︎

- A Gazetteer of the World, written by A.A. Braze (1856), states the inhabitants of Angot as Amhara. p.25 ↩︎

- British and foriegn state papers 1863-1864 Vol LIV. William Ridgway ↩︎

- Nuova Enciclopedia Italiana,1875 ↩︎

- Dye (1880), p. 519, map of Northern Abyssinia ↩︎

- The Political Crisis in Tigray, 1889-99 by Bairu Tafla ↩︎

- Rand McNally Atlas, 1895 ↩︎

- Peter J. Oestergaard; Kartographische Anstalt von F.A. Brockhaus, Berlin; Leipzig, 1920 ↩︎

- Assault on Rural Poverty: The Case of Ethiopia by Haileleul Getahun ↩︎

- Assault on Rural Poverty: The Case of Ethiopia by Haileleul Getahun ↩︎

- Popular Protest, Political Opportunities, and Change in Africa by Edalina Rodrigues Sanches ↩︎